Chapter 6

I Construction During The Settlement Years

II The Use Of Timber As A Structural Material

III Structural Steel

IV Concrete Technology

V Housing

VI Industrialised Pre-cast Concrete Housing

VII Ports And Harbours

VIII Roads

IX Heavy Foundations

X Bridges

XI Sewerage

XII Water Engineering

XIII Railways

XIV Major Buildings

XV Airports

XVI Thermal Power Stations

XVII Materials Handling

XVIII Oil Industry

XIX The Snowy Mountains Scheme

XX The Sydney Opera House

XXI The Sydney Harbour Bridge

XXII Hamersley Iron

XXIII North West Shelf

Sources and References

Index

Search

Help

Contact us

Modern architecture came comparatively late to Australia, and the 'heroic age' of modern masters like Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius in the 1920s and 1930s had relatively little impact here. But a milestone in the post-war architecture was ICI House in Melbourne (Fig. 49) designed by Bates Smart and McCutcheon in 1956. The responsible partner, the late Sir Osborne McCutcheon, was the first architectural Fellow of this Academy. The building achieved distinction for several reasons: it represented a break from the previous height limitations of 40 metres to 70 metres: it was the first major curtain wall structure in Melbourne, to counter the increasing costs of site labour, a modular system was adopted which incorporated lightweight prefabricated building components. The rigid frame structure was designed by Harvey Brown by methods developed at Purdue University, U.S.A., it was the first occasion in Melbourne when site welded joints were adopted for a major rigid frame building, and fire protection was provided by light-weight precast gypsum units.

Some years after completion a number of failures occurred in the blue/grey heat strengthened glass in the curtain walls. These failures were ultimately proved, after exhaustive tests by CSIRO, to have originated from minute nickel sulphide impurities in the glass.

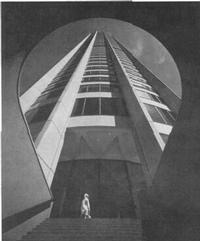

Further impetus to the modern idiom, came with the arrival in Australia in 1948 of Harry Seidler, who had trained at Harvard University under Gropius. In his Australia Square project, Sydney (Fig. 50) (1967), Seidler demonstrated his mastery at solving a central-city high-rise situation thus effectively introducing large scale modern architecture to the Australian public. By freeing the ground level of this previously congested inner city site, it won much-needed public open space, and its structural forms clearly evidenced the design imprint of the famed Italian engineer, Pier Luigi Nervi, who collaborated with Seidler on the scheme.

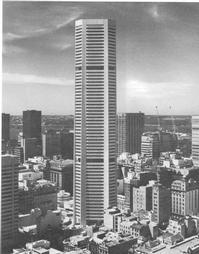

Several years later they again collaborated on the larger and more complex MLC Centre (1975) (Fig. 51), fronting Martin Place in Sydney, and incorporating a redesigned Theatre Royal. The high-rise office tower, octagonal in plan, its great structural corner shafts tapered towards the top, and the foyer ceilings to tower and theatre demonstrating anew Nervi's structural artistry, again allowed at street level significant public open space, here arranged on two levels. But Seidler went further and integrated the air-conditioning and service ducts into the concave-shaped beams that formed the spandrels to each floor, their deep reveals providing sun-protection for the offices within. It marked an overall design synthesis of structure and services rare in modern Australian architecture.

Organisations in Australian Science at Work - Bates, Smart and McCutcheon

People in Bright Sparcs - Brown, Harvey; Haskell, Prof. J. C.; McCutcheon, Sir Oswald; Nervi, Pier Luigi; Seidler, Harry

|

Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering |  |

© 1988 Print Edition pages 383 - 384, Online Edition 2000

Published by Australian Science and Technology Heritage Centre, using the Web Academic Resource Publisher

http://www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au/tia/385.html