Chapter 6

I Construction During The Settlement Years

II The Use Of Timber As A Structural Material

III Structural Steel

IV Concrete Technology

V Housing

VI Industrialised Pre-cast Concrete Housing

VII Ports And Harbours

VIII Roads

IX Heavy Foundations

X Bridges

XI Sewerage

XII Water Engineering

XIII Railways

XIV Major Buildings

XV Airports

XVI Thermal Power Stations

XVII Materials Handling

XVIII Oil Industry

XIX The Snowy Mountains Scheme

XX The Sydney Opera House

XXI The Sydney Harbour Bridge

XXII Hamersley Iron

XXIII North West Shelf

Sources and References

Index

Search

Help

Contact us

The section of this Chapter which is devoted specifically to roads, traces their history from the first track leading from Dawes Point around the west side of Sydney Cove to the technology applicable in 1986. Some of the early tracks were intended specifically for foot passage, while bullock teams created their own tracks. Then, as usage increased, those initial tracks were often upgraded for the use of horse-drawn carriages. Some of them still followed the rather disorderly and winding routes chosen by the leading bullocks. George Street, Sydney was one such example. Later, to give access to the more fertile areas, tracks were built to the west to Parramatta and, after the 1812 drought, further west still to the plains of Bathurst. This was a prodigious feat by Australia's first road construction engineer, William Cox who, with a small convict team, built a road across the rugged Blue Mountains in six months.

Establishment of the early roads led to the concurrent development of bridge engineering -the early structures being of the simple timber girder type. The first such bridge was attributed to Alt, with his bridge across the Tank Stream, somewhere near where it crossed the present Bridge Street. Section Nine traces the history of bridges, from those simple timber structures through to today's technology, where Australia's engineers are building some of the most sophisticated bridges in the world.

The construction of early ports was usually a relatively simple matter, due to the availability of deep sheltered water close to the shore and the relatively shallow draughts of the trading vessels. These ports usually took the form of land backed berths, using local timbers for piles and deck structures. While the berths were simple to construct, the construction of navigational aids for the vessels using them was anything but simple. Indeed, it often called for the construction of lighthouses on high positions on rugged and remote coastlines.

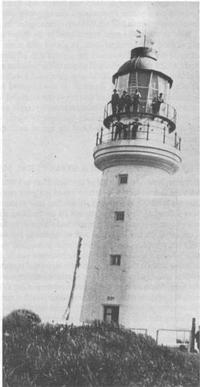

A particular example is the Cape Otway Lighthouse (Fig. 4) on the south coast of Victoria. During the 1840s, wrecks on the south coast were so numerous that the Admiralty issued an edict to Governor Sir George Gipps, which stated that unless a lighthouse was built on the Cape within three years, all ships coming from England to Melbourne would be instructed not to pass through the 'eye of the needle', but to approach Bass Strait from the east by diverting around the southern end of Tasmania. Apart from building the lighthouse, access to the Cape presented a formidable challenge. It was initially achieved, on his third attempt, by Superintendant La Trobe, later Victoria's first Governor.

While access was difficult, construction of the lighthouse was even more difficult. La Trobe envisaged a cast iron structure but lack, in Australia, of technology in this field and the inevitable delays which would have occurred had materials been imported from England, forced the decision to build from local materials. It was to be a conventional masonry structure with a fluted base. Fortunately there was an outcrop of good quality sandstone close by. A contract for construction was let to a Geelong mason called MacGillivray for £11,995, a figure markedly lower than tenders submitted by his competitors. Landing his first supplies from a small boat on a rocky coast in rough seas, nearly ended in disaster. Logistical difficulties generally, together with a disconsolate work force and a looming significant financial loss, led to such a poor performance that the contract was foreclosed. The Government took over the work and with twenty-three stonemasons, one carpenter, one blacksmith, five bullock drivers, seven quarry hands and ten labourers, completed the task in 1848 at a cost of £4,300.

People in Bright Sparcs - Alt, Capt. Theodore Henry; Cox, William; Gipps, Gov. George; Holland, Sir John; La Trobe, Superintendent Charles Joseph; MacGillivray, Alistair

|

Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering |  |

© 1988 Print Edition pages 315 - 317, Online Edition 2000

Published by Australian Science and Technology Heritage Centre, using the Web Academic Resource Publisher

http://www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au/tia/315.html