Chapter 4

I Management Of Native Forests

II Plantations-high Productivity Resources

III Protecting The Resource

IV Harvesting The Resource

V Solid Wood And Its Processing

VI Minor Forest Products

VII Reconstituted Wood Products

VIII Pulp And Paper

IX Export Woodchips

X Future Directions

XI Acknowledgements

References

Index

Search

Help

Contact us

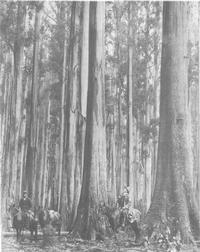

Starting on the Australian Alps in southern NSW and extending well into the eastern part of Victoria were large wet sclerophyll forests with alpine ash (E. delegatensis) occurring between 900 and 1500 metres and, further south, mountain ash (E. regnans), at altitudes up to about 1100 metres and in high rainfall areas. In the foothill areas of the Alps and in the Central Highlands of Victoria dry sclerophyll mixed eucalypt forests occurred with messmate stringybark (E. obliqua) being widespread, in association with other stringybarks, peppermints and gums. The ash species also occurred in Tasmania but with common names different from those in Victoria, E. delegatensis being generally known as white top and E. regnans as swamp gum. Other important species in Tasmania were messmate stringybark, Tasmanian blue gum, black-wood (Acacia melanoxylon), myrtle beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii) and the softwoods Huon pine, King William pine (Athrotaxis selaginoides) and celery top pine (Phyllocladus aspleniifolius).

South Australia and Northern Territory possessed only small forest areas of commercial significance but in the south-west of Western Australia were two very important resources. In the higher rainfall area to the south was the karri forest (E. diversicolor) and to the north of this the larger forests of jarrah. Pure stands were common in both.

As well as the forest species mentioned some others having valuable wood properties were found in less concentrated stands in the woodland areas, for example the very widespread river red gum (E. camaldulensis), the red ironbark (E. sideroxylon) of inland NSW and the yellow gum (E. leucoxylon) in South Australia.

The first sawmills were introduced in the 1820s and used water-powered vertical frame saws, essentially just a mechanized version of pit-sawing. Steam power followed and about 1850 the first circular saws appeared and sawmills began to become more widespread throughout the colonies. The discovery of gold naturally provided much stimulus to the industry, but placed a heavy demand on the forest resource, particularly close to the towns and mining areas. Not only did the mines require timber for fuel and for structural use but the rapidly increasing population also needed housing and furniture as well as fuel and cleared land. The upsurge in economic growth in the UK and North America in the second half of the nineteenth century also had its effects. Export of quality timbers such as jarrah increased and still more forest land was cleared for the production of agricultural exports. Another important factor was the demand for sleepers and large structural timbers for the rapidly developing railway systems, both in Australia and overseas.

Timber cutting at this time was rarely done with the future productivity of the resource in mind. Only the best trees were taken and only the best parts of their stems utilized. Logging residues were left where they fell and when fires occurred they tended to be of greater than normal intensity and killed many trees or damaged them, so that they became susceptible to disease and insect attack. Where the trees had been removed non-commercial understorey species often took over, making access difficult and preventing regeneration. In the dry sclerophyll forests, where some regeneration was able to occur, it was generally under over-crowded conditions unfavourable to healthy development and high productivity. Grazing in the forests was common, but unfortunately this was often accompanied by periodic firing to promote grass growth. Where such fires -or those lit by the many new settlers to clear their blocks -became out of control extensive forest damage generally resulted, as there was little policing of such activities and no fire-fighting organization.

|

Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering |  |

© 1988 Print Edition page 195, Online Edition 2000

Published by Australian Science and Technology Heritage Centre, using the Web Academic Resource Publisher

http://www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au/tia/205.html